VIEW-hub now tracks global introductions and use of products preventing respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) disease in infants, including monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) and the maternal vaccine. This topic page explores the benefits of these prevention strategies and their introduction.

Table of Contents

- Background

- RSV and VIEW-hub

- Monoclonal Antibodies

- Maternal Vaccination

- WHO Prequalification and Recommendations

- Next Steps

- Key Takeaways

- Additional Resources and References

Background

RSV is a respiratory virus that infects almost every child by their second birthday [1]. Similarly to many other respiratory viruses, RSV transmission typically follows seasonal patterns [2]. RSV infections usually occur over a period of several months each year—in temperate climates, there is clearer seasonality (late fall and winter), while sub-tropical and tropical climates have less clear seasonality patterns [3]. Many cases of RSV are mild, with symptoms similar to the common cold, but it can become serious and even life-threatening, particularly among infants, young children, and older adults.

Disease Burden

Each year, RSV is responsible for over 3.6 million hospitalizations and approximately 100,000 deaths globally among children under 5 years [3]. The overwhelming majority of RSV-attributed acute lower respiratory infections (LRTIs) and deaths occur in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs)—more than 95% and 97%, respectively [4]. A large international case-control study found that RSV was responsible for nearly one-third of severe or very severe pneumonia cases among hospitalized children between 1–59 months of age [5]. This burden may be even higher among very young children, with RSV estimated to account for nearly one-half of acute respiratory illnesses among children under 6 months living in LMICs [6]. Further, it is estimated that one in every 50 deaths in children under 5 years and one in every 28 deaths in children between 28 days and 6 months of age is attributable to RSV [4].

Prevention

As there is no specific treatment for RSV, prevention is critical for reducing disease burden. In 1998, the first prophylactic measure for RSV became available, a monoclonal antibody (mAb) targeted directly at RSV to prevent disease. In 2023 and 2025, other mAbs were licensed and are now available more widely. While all children are at risk of RSV infection, the high cost of mAbs means only children living in high-income countries or high-risk children (such as those born prematurely and those with underlying medical conditions) have access to them. In 2023, a maternal vaccine became available that also provides passive immunization to infants through maternally acquired antibodies, which further expands options for children living in LMICs [7].

RSV and VIEW-hub

The latest VIEW-hub module tracks these RSV prevention strategies. Data include which countries have made mAbs or the maternal vaccine available, either through their national immunization program or the private market, and which countries are planning to do so. Data are also available on which products are in use, the timing of maternal vaccination (seasonal versus year-round), and the target population for mAbs. As more countries introduce RSV prevention products, VIEW-hub will track progress toward protecting those infants most vulnerable to severe disease in all parts of the world.

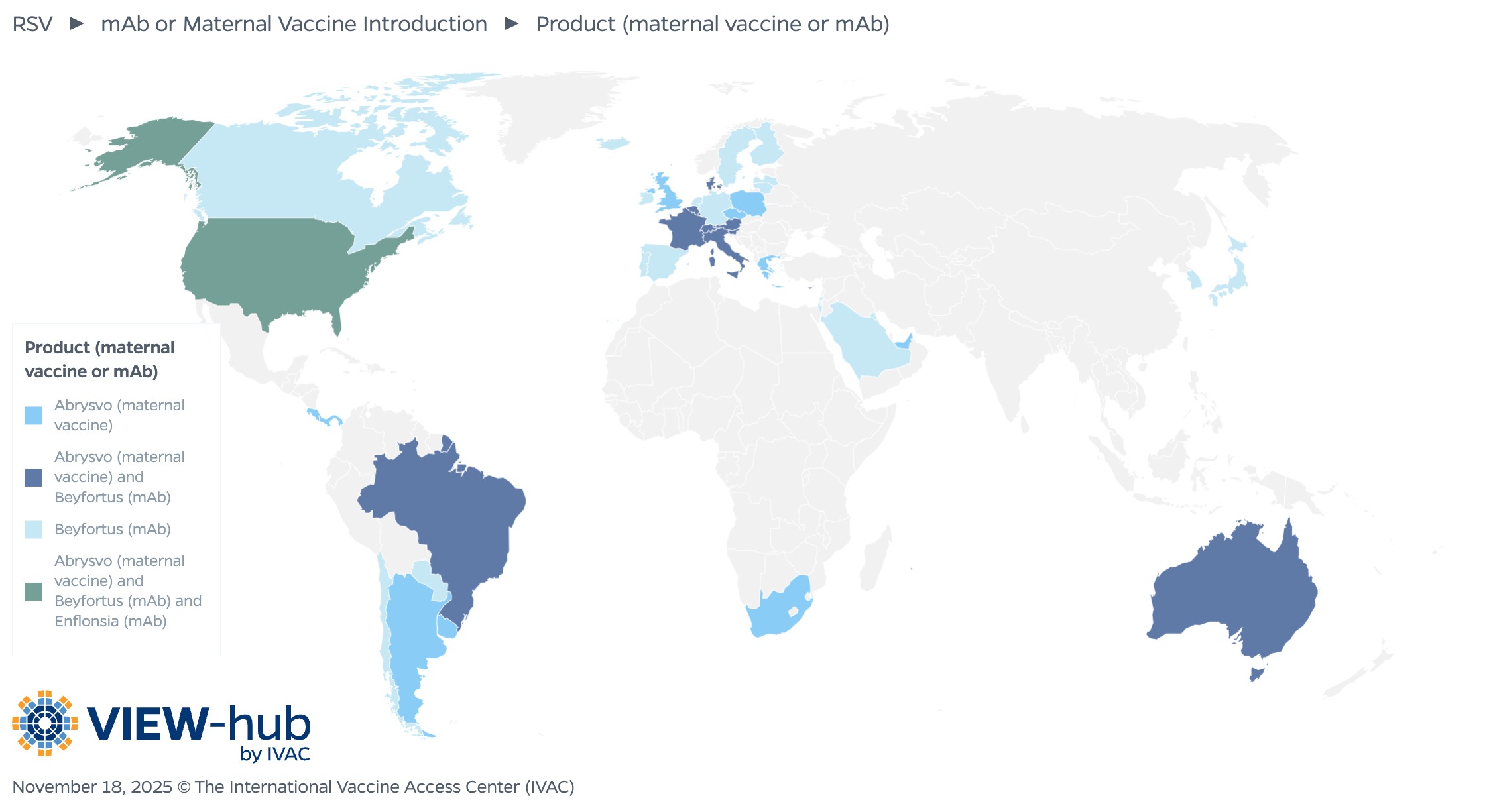

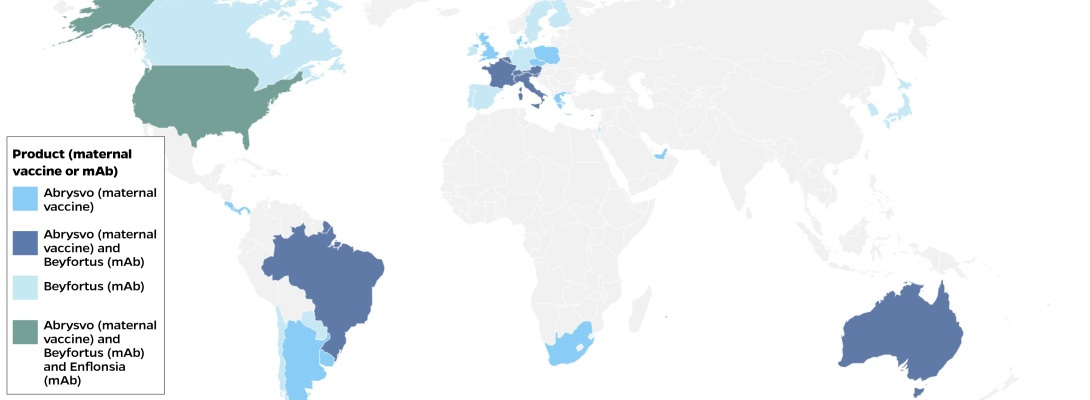

As of November 2025, 41 countries have made either the maternal vaccine or mAbs available through their national immunization program or the private market. The countries that have introduced RSV products are primarily high-income countries (37), along with a handful (4) of upper middle-income countries. Of the countries that have introduced an RSV product, 18 (44%) have introduced the mAb Beyfortus (nirsevimab); 11 countries have introduced the maternal vaccine Abrysvo; and 11 countries have introduced both Beyfortus and Abrysvo.

Monoclonal Antibodies

mAbs do not activate the immune system like vaccines but provide immediate short-term protection for approximately five months following administration, covering the length of a typical RSV season. A single mAb dose is administered to infants during or shortly before their first RSV season (or during an older child’s second RSV season if they are at increased risk of severe disease). Recently approved mAbs for use in the United States include nirsevimab and clesrovimab, replacing the first mAb, palivizumab, which is scheduled to be discontinued at the end of 2025 [8,9].

Rollout and Uptake

Since the 2023–24 RSV season, nirsevimab has been introduced in several countries, including Spain, France, and the United States, among others. Uptake has varied, with Spain reporting approximately 90% uptake among eligible children compared to just 51% uptake in the United States during the 2023–24 season [10].

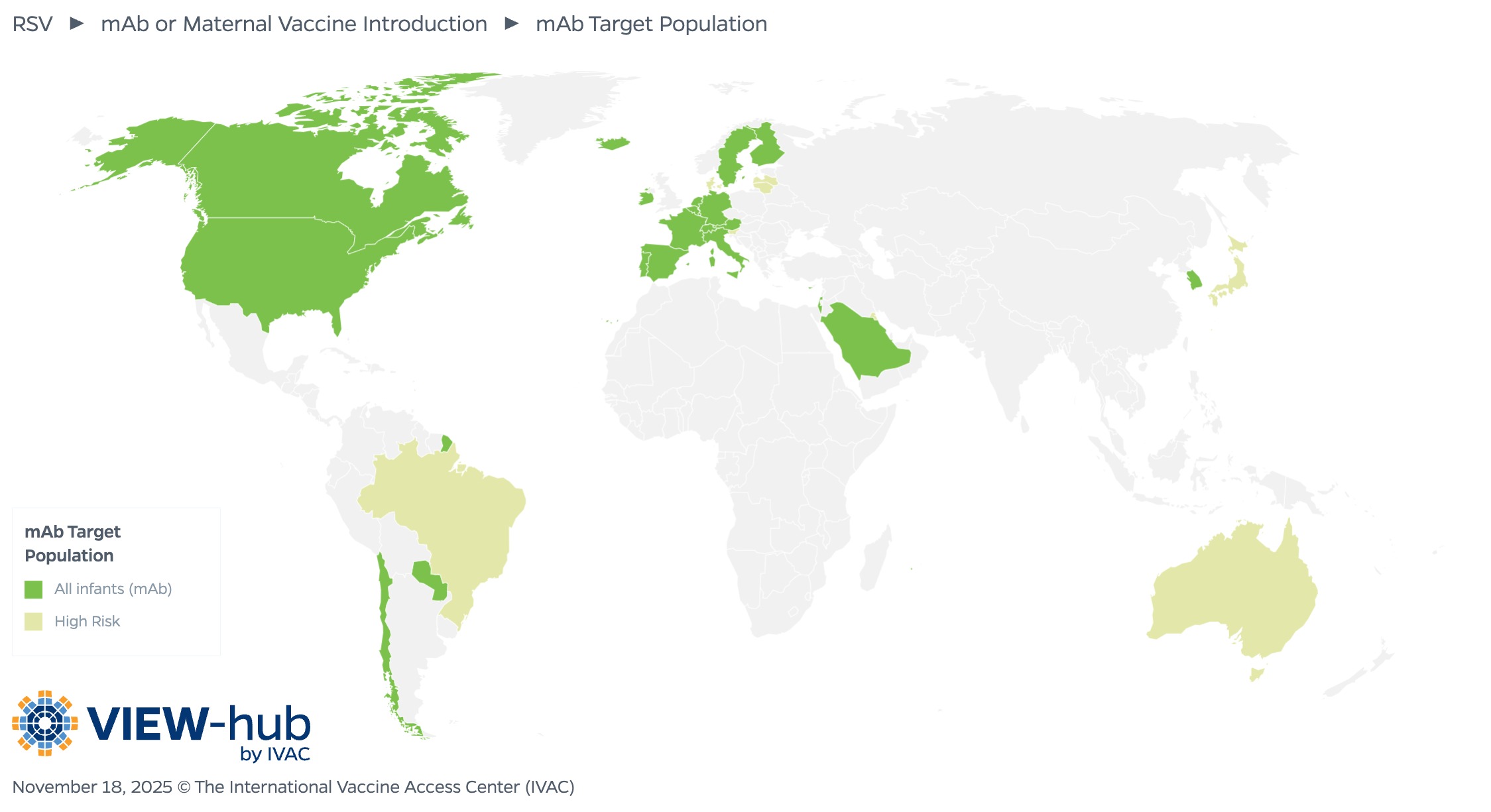

In countries that have introduced mAbs, most (22 countries, or 73%) have made them available for all infants. Eight countries target infants and young children at increased risk of severe RSV disease, with the product administered before or during the RSV season.

Impact

mAbs have been shown to offer significant protection against severe disease. An analysis of the first 3 months of the 2023–24 campaign in Galicia, Spain, showed 82% effectiveness (95% CI: 65.6–90.2) against RSV-associated LRTI hospitalization and 86.9% effectiveness (95% CI: 69.1–94.2) against severe RSV-associated LRTI hospitalization [11]. These findings align with clinical trial results demonstrating 74.5% efficacy (95% CI: 49.6–87.1) [12]. Beyond keeping children healthy, these results also demonstrate how the use of mAbs can reduce strain on the health system, an especially important consideration during respiratory season when resources are already stretched thin.

Modeling estimates project that mAbs could avert up to 356,057 deaths across 131 LMICs over a 10-year period, averting 55% of global RSV deaths among infants under 6 months [13].

Maternal Vaccination

Maternal RSV vaccination works by stimulating the production of antibodies to RSV in pregnant women, which are then transferred to their infants through the placenta. The vaccine is administered during the third trimester and infants are protected for up to six months after birth.

Rollout and Uptake

Maternal vaccination was first introduced in 2024. In Argentina, more than half of eligible pregnant women received the vaccine during the 2024 RSV season [14]. Uptake in the United States, however, was suboptimal—only 1 in 3 eligible pregnant women received the vaccine during the 2024–25 RSV season [15].

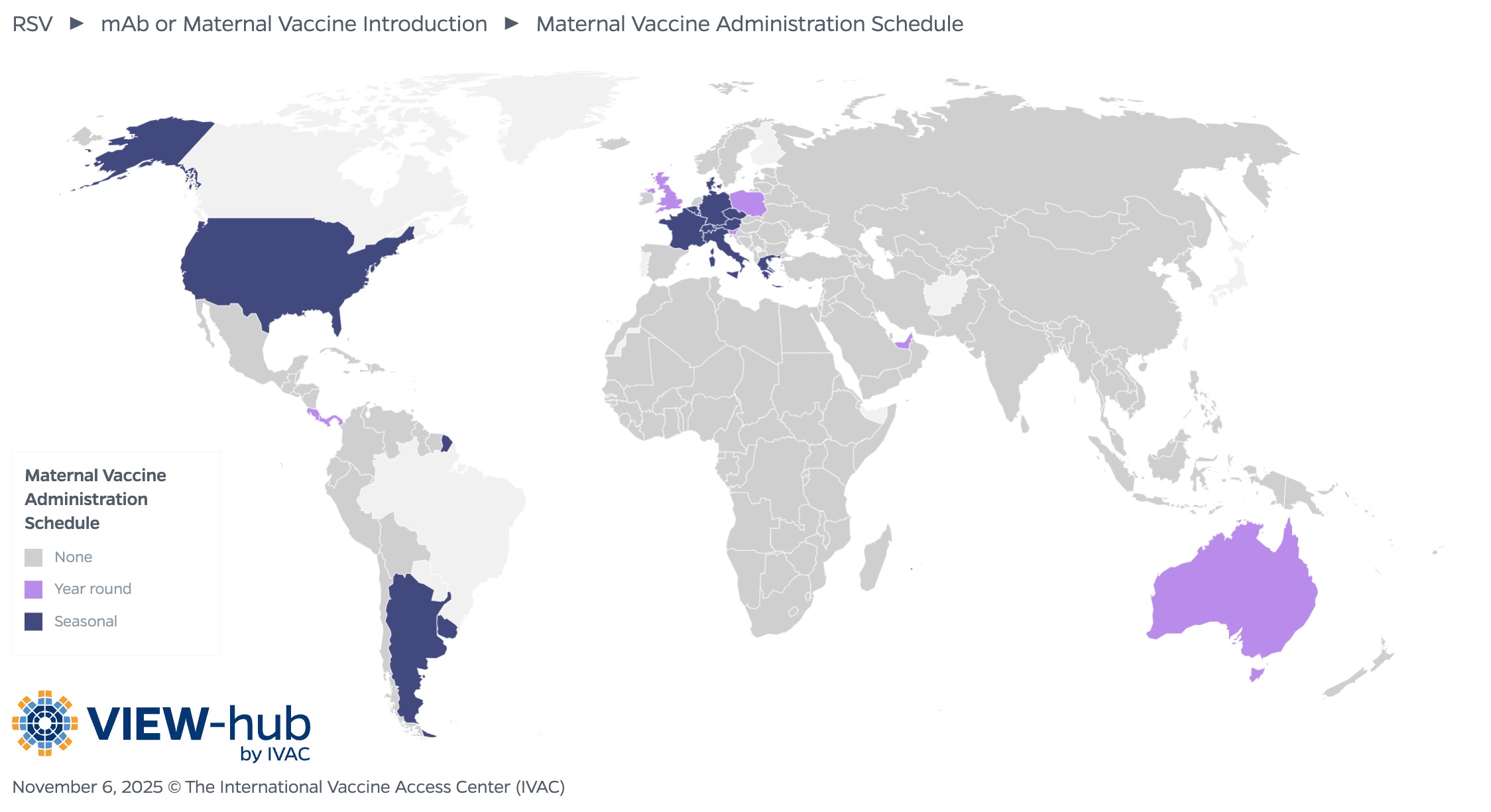

Of the countries that have introduced the maternal vaccine, most (14, or 64%) utilize a seasonal vaccination schedule, administering the vaccine only during months preceding or overlapping with the local RSV transmission season, while the remaining eight countries (36%) administer the vaccine year-round. The recommended timing of administration varies, though most countries administer between 32–36 weeks (13, or 52%) or 24–36 weeks (8, or 32%).

Impact

Maternal vaccination is highly effective at protecting infants from severe disease. A retrospective case-control study in Argentina found 78.6% effectiveness (95% CI: 62.1–87.9) against RSV-associated lower respiratory tract disease (LRTD) requiring hospitalization among infants under 3 months and 71.3% (95% CI: 53.3–82.3) among infants under 6 months [16]. These results confirm that the immunization offered by maternal vaccination can protect an infant in the earliest months of life, the period when children are most vulnerable.

A modeling study estimated that maternal vaccination could avert 2.97 million non-severe RSV cases, 2.63 million severe cases, 2.03 million hospitalizations, and 126,552 deaths among infants under 6 months across 131 LMICs over 10 years [13]. This would equal 17% of severe RSV cases and 25% of RSV-related deaths among infants under 6 months [13].

WHO Prequalification and Recommendations

The high cost and limited supply of RSV prevention products originally restricted their use to high-income countries. However, in March 2025, the first maternal RSV vaccine was prequalified by WHO, a milestone that will hopefully expand access to children everywhere [17].

Following this prequalification, WHO released a position paper in May 2025 outlining recommendations for RSV immunization, including mAbs [18]. Specific recommendations include:

- All countries should introduce products to prevent severe RSV disease among young infants.

- In countries implementing maternal vaccination, a single dose of RSV vaccine should be administered during the third trimester, ideally at least 2 weeks before delivery to allow sufficient time for antibody transfer.

- In countries introducing mAbs, a single dose should be administered at birth (or at the earliest opportunity) to infants up to 12 months who are entering their first RSV season.

The recommendations also clarify that an infant whose mother was vaccinated during pregnancy typically should not receive a dose of mAb. Additionally, although a seasonal approach to immunization can be implemented in countries with established seasonal patterns of RSV transmission, it may be more feasible and cost-effective to administer RSV immunization products throughout the year in tropical or subtropical regions where RSV disease occurs throughout the year.

Next Steps

Now that RSV vaccination products have been introduced, efforts should focus on ensuring that children everywhere have access to these products and promoting uptake through targeted communication strategies.

To date, the high cost of these products has been a significant constraint. Following the WHO prequalification, Gavi announced a funding window for establishing an RSV maternal vaccine program and has recently entered the design phase of this new program [19,20]. A multi-dose vial of the maternal RSV vaccine is currently in development, a presentation that would reduce manufacturing and distribution costs. Support from Gavi and other donors will be critical to enable introduction in LMICs, especially as other new vaccines compete for limited funding. RSV mAbs are prohibitively expensive, and there is not yet a funding mechanism available to support their introduction in LMICs.

As we have seen in the United States, availability of an RSV vaccine does not guarantee its uptake. Pregnant and lactating women who may be hesitant to receive the RSV vaccine have expressed concerns about its safety [21]. Evidence from placebo-controlled trials suggests risks of severe adverse events (such as congenital abnormalities or intrauterine growth restriction) were similar between vaccinated and placebo groups, with the frequency of events being rare in both groups, though monitoring will continue [22]. This highlights the need for focused community sensitization prior to vaccine introduction. These efforts should target both pregnant women as well as health care workers, who are important drivers of vaccine uptake among this population [23].

Key Takeaways

- Due to high disease burden and the unavailability of RSV disease-specific treatment, prevention of RSV is critical to reduce morbidity and mortality among infants and children.

- mAbs and maternal vaccination have been demonstrated to be effective at protecting young infants from severe disease and reducing the strain on the health system.

- Although WHO’s prequalification of the maternal RSV vaccine will hopefully expand access to these products in LMICs, sustainable funding will be critical to facilitate their introduction.

- Community sensitization efforts will be key to ensuring high uptake of RSV prevention products once they are more widely available.

Additional Resources

WHO RSV Information (fact sheet, Q&A)

References

1. Respiratory Syncytial Virus (RSV) – NFID. https://www.nfid.org/. Accessed October 14, 2025. https://www.nfid.org/infectious-disease/rsv/

2. Chadha M, Hirve S, Bancej C, et al. Human respiratory syncytial virus and influenza seasonality patterns-Early findings from the WHO global respiratory syncytial virus surveillance. Influenza Other Respir Viruses. 2020;14(6):638-646. doi:10.1111/irv.12726

3. Respiratory syncytial virus (RSV). https://www.who.int/. Accessed October 14, 2025. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/respiratory-syncytial-virus-(rsv)

4. Li Y, Wang X, Blau DM, et al. Global, regional, and national disease burden estimates of acute lower respiratory infections due to respiratory syncytial virus in children younger than 5 years in 2019: a systematic analysis. The Lancet. 2022;399(10340):2047-2064. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(22)00478-0

5. O’Brien KL, Baggett HC, Brooks WA, et al. Causes of severe pneumonia requiring hospital admission in children without HIV infection from Africa and Asia: the PERCH multi-country case-control study. The Lancet. 2019;394(10200):757-779. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(19)30721-4

6. Lutz CS, Zhang H, Knoll MD, Sparrow E, Chen H, Feikin D. Respiratory Syncytial Virus Positivity Among Hospital Admissions for Acute Respiratory Illness in Children Younger than 5 Years of Age in Low- and Middle-Income Countries: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. SSRN. Preprint posted online 2025. doi:10.2139/ssrn.5395608

7. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. FDA Approves First Vaccine for Pregnant Individuals to Prevent RSV in Infants. FDA. August 22, 2023. Accessed November 5, 2025. https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/fda-approves-first-vaccine-pregnant-individuals-prevent-rsv-infants

8. U.S. FDA Approves Merck’s ENFLONSIATMTM (clesrovimab-cfor) for Prevention of Respiratory Syncytial Virus (RSV) Lower Respiratory Tract Disease in Infants Born During or Entering Their First RSV Season. Merck.com. Accessed October 14, 2025. https://www.merck.com/news/u-s-fda-approves-mercks-enflonsia-clesrovimab-cfor-for-prevention-of-respiratory-syncytial-virus-rsv-lower-respiratory-tract-disease-in-infants-born-during-or-entering-their-fir/

9. Sobi discontinues RSV injection Synagis | AAP News | American Academy of Pediatrics. Accessed October 14, 2025. https://publications.aap.org/aapnews/news/32817/Sobi-discontinues-RSV-injection-Synagis?autologincheck=redirected

10. Trusinska D, Lee B, Ferdous S, et al. Real-world uptake of nirsevimab, RSV maternal vaccine, and RSV vaccines for older adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. eClinicalMedicine. 2025;84:103281. doi:10.1016/j.eclinm.2025.103281

11. Ares-Gómez S, Mallah N, Santiago-Pérez MI, et al. Effectiveness and impact of universal prophylaxis with nirsevimab in infants against hospitalisation for respiratory syncytial virus in Galicia, Spain: initial results of a population-based longitudinal study. The Lancet Infectious Diseases. 2024;24(8):817-828. doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(24)00215-9

12. Hammitt LL, Dagan R, Yuan Y, et al. Nirsevimab for Prevention of RSV in Healthy Late-Preterm and Term Infants. N Engl J Med. 2022;386(9):837-846. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2110275

13. Baral R, Higgins D, Regan K, Pecenka C. Impact and cost-effectiveness of potential interventions against infant respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) in 131 low-income and middle-income countries using a static cohort model. BMJ Open. 2021;11(4):e046563. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2020-046563

14. Pecenka C, Sparrow E, Feikin DR, et al. Respiratory syncytial virus vaccination and immunoprophylaxis: realising the potential for protection of young children. The Lancet. 2024;404(10458):1157-1170. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(24)01699-4

15. National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases, CDC. Implementation and Uptake of Nirsevimab and Maternal Vaccine for Infant Protection from RSV. Presented at: June 25, 2025. Accessed November 5, 2025. https://www.cdc.gov/acip/downloads/slides-2025-06-25-26/02-Peacock-Mat-Peds-RSV-508.pdf

16. Pérez Marc G, Vizzotti C, Fell DB, et al. Real-world effectiveness of RSVpreF vaccination during pregnancy against RSV-associated lower respiratory tract disease leading to hospitalisation in infants during the 2024 RSV season in Argentina (BERNI study): a multicentre, retrospective, test-negative, case–control study. The Lancet Infectious Diseases. 2025;25(9):1044-1054. doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(25)00156-2

17. WHO prequalifies first maternal respiratory syncytial virus vaccine. Accessed October 14, 2025. https://www.who.int/news/item/19-03-2025-who-prequalifies-first-maternal-respiratory-syncytial-virus-vaccine

18. World Health Organization. WHO Position Paper on Immunization to Protect Infants against Respiratory Syncytial Virus Disease, May 2025.; 2025:193-218. https://iris.who.int/server/api/core/bitstreams/96ec533a-de56-4e1a-8e01-420afda0b683/content

19. Gavi Board focuses on health impact as priority guiding principle in a resource constrained world. October 14, 2025. Accessed October 15, 2025. https://www.gavi.org/news/media-room/gavi-board-focuses-health-impact-priority-guiding-principle-resource-constrained

20. Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance. Gavi and partners commence design of RSV maternal vaccine programme. November 5, 2025. Accessed November 5, 2025. https://www.gavi.org/news/media-room/gavi-and-partners-commence-design-rsv-maternal-vaccine-programme

21. Limaye RJ, Singh P, Fesshaye B, Karron RA. Lessons learned from COVID-19 vaccine acceptance among pregnant and lactating women from two districts in Kenya to inform demand generation efforts for future maternal RSV vaccines. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2024;24(1):221. doi:10.1186/s12884-024-06425-y

22. Phijffer EW, de Bruin O, Ahmadizar F, et al. Respiratory syncytial virus vaccination during pregnancy for improving infant outcomes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2024;5(5):CD015134. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD015134.pub2

23. Etti M, Calvert A, Galiza E, et al. Maternal vaccination: a review of current evidence and recommendations. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2022;226(4):459-474. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2021.10.041