Vaccination against human papillomavirus (HPV) is critical for reducing cases and deaths of cervical cancer, the fourth most common cancer among women globally [1]. As persistent, high-risk strains of HPV are the cause of nearly all cervical cancer cases [2], vaccination is a major pillar of the World Health Organization (WHO)’s global strategy to eliminate cervical cancer [3]. Its potential health impact is demonstrated by recent findings that cervical cancer deaths in the United States were reduced by 62% among women under 25, the first cohort of women to be widely vaccinated against HPV [4]. Deaths from cervical cancer are expected to continue to fall over time as this group of women ages.

Table of Contents

- Background

- HPV Vaccine Coverage

- Global Adoption of Single-Dose Schedules

- Benefits of a Single-Dose Schedule

- Key Takeaways

- Additional Resources

Background

Unlike most routine immunizations, HPV vaccines target adolescents between the ages of 9-14 years, with the goal of protecting this population before they become sexually active. Current WHO recommendations prioritize girls for HPV vaccination, given past vaccine supply constraints, although many countries target both girls and boys. The original WHO recommendation was for a three-dose schedule, which was changed to a two-dose schedule after evidence emerged demonstrating its noninferiority [5].

HPV Vaccine Coverage

Although low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) carry a disproportionate cervical cancer burden, these countries were slower to introduce HPV vaccines into national immunization programs [6]. Global coverage of HPV vaccines lags behind targets, with an estimated 31% of girls having received at least one dose in 2024 [7]. The programmatic complexities and substantial costs of a multi-dose HPV vaccine series have contributed to inadequate coverage [8]. Promisingly, inequitable access to HPV vaccines in LMICs has started to improve, partly thanks to the adoption of a single-dose schedule that provides comparable protection with additional financial and programmatic benefits [7].

Global Adoption of Single-Dose Schedules

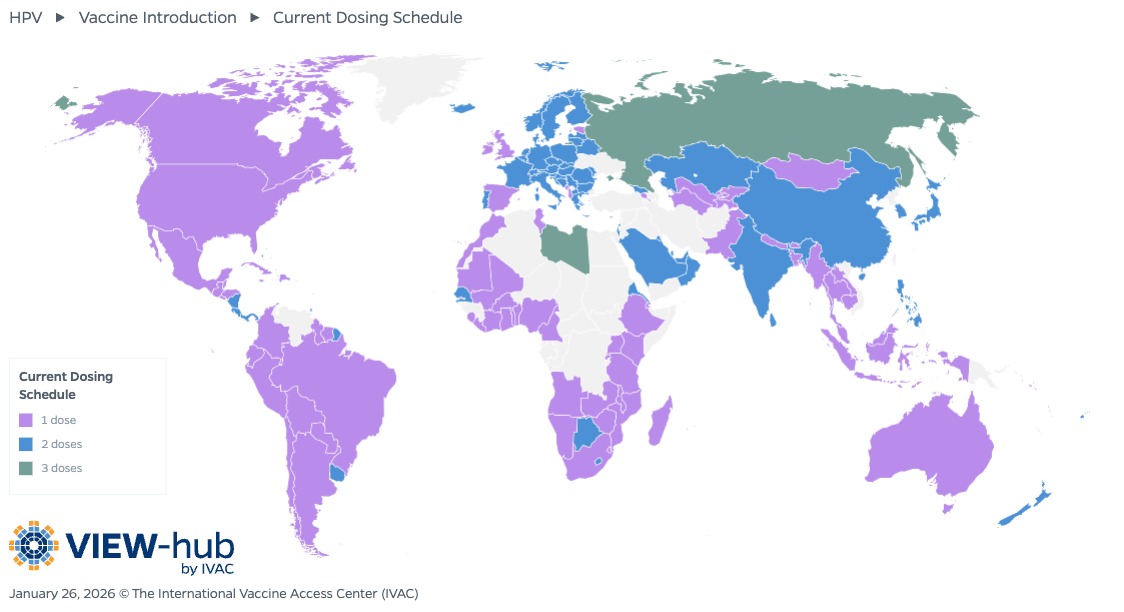

In December 2022, the WHO updated its position paper on HPV vaccination to include a single-dose schedule as an off-label alternative for girls and boys between 9 and 20 years old, excluding those who are HIV-infected or otherwise immunocompromised [9]. HPV vaccine dosing schedules are visualized on the VIEW-hub map below.

Of the 164 countries that have introduced HPV vaccines into their national immunization programs or have introduced subnationally, 89 countries (54%) use a single-dose schedule as of January 2026. 21 of these countries introduced the HPV vaccine into their national immunization programs using a single-dose schedule, while the majority (68, or 76%) initially introduced HPV vaccines with a two- or three-dose schedule but switched to a single-dose schedule after the updated WHO recommendation.

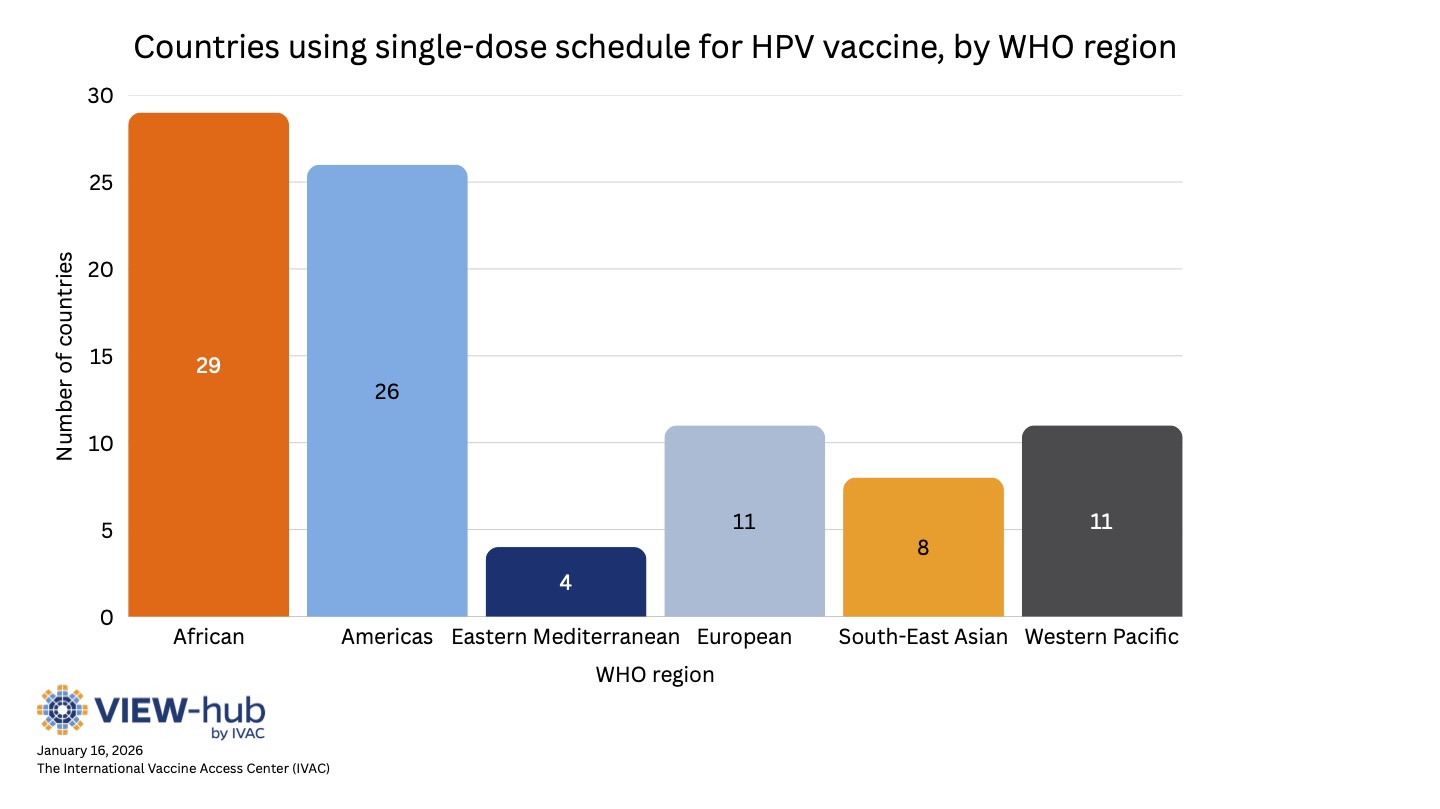

Most countries using a single-dose schedule are middle-income countries (38% lower-middle-income and 36% upper-middle income), though low-income and high-income countries are also represented (13% and 12%, respectively). Most Gavi-eligible countries have adopted a single-dose schedule (34 of 37, or 92%). Current Gavi funding guidelines allow countries to select either a one- or two-dose schedule, though they encourage the use of a single-dose schedule [10]. Countries using single-dose schedules are also spread geographically, with all WHO regions represented, as seen in the graph below.

Among countries that use a single-dose schedule:

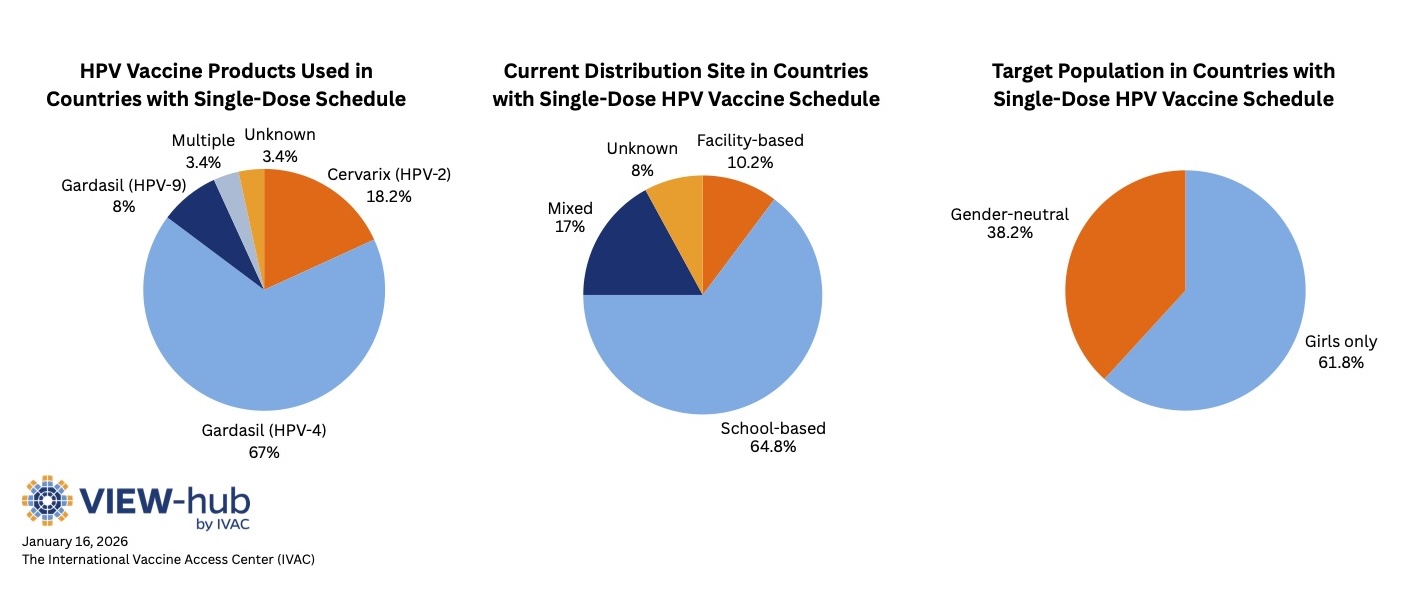

- The quadrivalent HPV vaccine (Gardasil 4) is the most common (used in 59 countries).

- About two-thirds of countries implement HPV vaccines through school-based delivery, rather than through health facilities.

- Most countries target only girls in their programs, while the rest have gender-neutral programs (targeting both boys and girls).

Although several high-income countries adopted a single-dose schedule following the WHO recommendation—Australia, Canada, Ireland, Spain, the United Kingdom, and the United States—many other high-income countries continue to use a two-dose schedule.

Benefits of a Single-Dose Schedule

Lasting Protection

The inclusion of a single-dose schedule in WHO’s HPV vaccine recommendations was based on multiple studies finding that one dose of the HPV vaccine can provide comparable efficacy and duration of protection to a two-dose schedule [11]. Researchers have found that one dose of HPV vaccine can provide 92% vaccine efficacy against persistent HPV 16 and 18 infection, a proxy for protection against cervical cancer, with no statistically significant differences in efficacy between 1, 2, or 3 doses [12]. These results are consistent across various trials [13,14].

Studies following women over time found that a single dose of the HPV vaccine continued to provide stable immune response throughout the study period [15], with one study following women for 16 years [16]. Based on this evidence, researchers project that a single dose of the HPV vaccine can prevent HPV infection for at least 20 years (and likely longer) after vaccination, protecting women during the time when they are most at risk [16].

Simplified Implementation

HPV vaccination targets adolescents between 9 and 14 years old, a population that generally has fewer interactions with routine immunization programs, and so these programs are typically more complicated than routine immunization programs for young children. A single-dose schedule would eliminate some of these complexities, such as the burdensome task of tracking and following up with girls who are overdue for their second dose.

Economic Savings

From a financial perspective, since the high price tags associated with HPV immunization are driven largely by the cost of procuring the vaccine itself [17], this expense would be essentially halved with the implementation of a single-dose schedule. Another significant cost of HPV vaccination programs is service delivery. Unlike most other routine vaccines, HPV vaccines are often administered in community settings, such as schools, to most effectively reach the target population, requiring health workers to travel to vaccination sites. HPV vaccination programs also require health workers to undergo additional training and perform social mobilization activities on top of their normal work duties. Modeling analyses demonstrate that a single-dose schedule can greatly lower the cost of delivering HPV vaccines by decreasing the number of vaccination sessions and thereby reducing per diems and other payments to health workers, vehicle rental and fuel costs, and costs associated with cold chain maintenance and waste management [18]. Analysis of HPV vaccination in four LMICs estimated that switching from a two-dose to a single-dose schedule increases the cost per dose but decreases the cost per fully immunized adolescent by up to 50% [19]. These cost savings would be especially beneficial in non-Gavi-eligible countries as well as those expected to transition out of Gavi support. Alternatively, cost savings could be reinvested to provide catch-up HPV vaccination to older girls, a strategy that would help to accelerate cervical cancer elimination.

Key Takeaways

- Compared to a multi-dose schedule, a single dose of HPV vaccine provides comparable efficacy and duration of protection.

- More than 80% of Gavi-eligible countries and half of all countries that have introduced HPV vaccination use a single-dose schedule, illustrating the broad appeal of this approach.

- Countries that have yet to introduce HPV vaccination should consider the use of a single-dose schedule to address existing financial and programmatic barriers to introduction.

- Countries that have already introduced HPV vaccination should consider switching to a single-dose schedule to optimize program implementation and increase coverage, accelerating progress toward cervical cancer elimination goals.

Additional Resources

The Power of a Single Dose: Evidence for a Single-Dose HPV Vaccine Schedule [IVAC]

References

- World Health Organization. Cervical cancer. World Health Organization. Published March 5, 2024. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/cervical-cancer

- National Cancer Institute. Cervical Cancer Causes, Risk Factors, and Prevention. National Cancer Insititute. Updated August 2, 2024. https://www.cancer.gov/types/cervical/causes-risk-prevention

- World Health Organization. Global strategy to accelerate the elimination of cervical cancer as a public health problem. World Health Organization. Published November 17, 2020. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240014107

- Dorali P, Damgacioglu H, Clarke MA, et al. Cervical cancer mortality among US women younger than 25 years, 1992-2021. JAMA. 2024;333(2):165-166. https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jama/fullarticle/2827212

- WHO Report. Human papillomavirus vaccines: WHO position paper, October 2014—recommendations. Vaccine. 2015;33(36):4383-4384. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0264410X14016181

- Borda H, Bloem P, Akaba H, et al. Status of HPV disease and vaccination programmes in LMICs: Introduction to special issue. Vaccine. 2024;42(S2):S1-S8. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0264410X23012756#b0165

- World Health Organization. Progress and challenges with Achieving Universal Immunization Coverage. World Health Organization. Published July 15, 2025. https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/progress-and-challenges

- Gallagher KE, LaMontagne DS, Watson-Jones D. Status of HPV vaccine introduction and barriers to country uptake. Vaccine. 2018;36(32):4761-4767. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2018.02.003

- World Health Organization. Human papillomavirus vaccines: WHO position paper, December 2022. World Health Organization. Published December 16, 2022. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/who-wer9750-645-672

- Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance. Human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine market shaping roadmap. Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance. Published March 2024. https://www.gavi.org/news-resources/knowledge-products/human-papillomavirus-hpv-vaccine-market-shaping-roadmap

- Stanley M, Schuind A, Muralidharan KK, et al. Evidence for an HPV one-dose schedule. Vaccine. 2024;42(S2):S16-S21. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0264410X24000586

- Barnabas RV, Brown ER, Onono MA, et al. Efficacy of single-dose human papillomavirus vaccination among young African women. NEJM Evid. 2022;1(5). https://evidence.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/EVIDoa2100056

- Jiamsiri S, Rhee C, Seon Ahn H, et al. Community intervention of a single-dose or 2-dose regimen of bivalent human papillomavirus vaccine in schoolgirls in Thailand: Vaccine effectiveness 2 years and 4 years after vaccination. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr. 2024;67:346-357. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/39529526/

- Barnabas RV, Brown ER, Onono MA, et al. Durability of single-dose HPV vaccination in young Kenyan women: Randomized controlled trial 3-year results. Nat Med. 2023;29(12):3224–3232. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10719107/

- Watson-Jones D, Changalucha J, Maxwell C, et al. Durability of immunogenicity at 5 years after a single dose of human papillomavirus vaccine compared with two doses in Tanzanian girls aged 9-14 years: Results of the long-term extension of the DoRIS randomised trial. Lancet Glob Health. 2025;13(2):e319-e328. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/39890232/

- Porras C, Romero B, Kemp T, et al. HPV16/18 antibodies 16-years after single dose of bivalent HPV vaccination: Costa Rica HPV vaccine trial. JNCI Monographs. 2024;2024(67):329-336 https://academic.oup.com/jncimono/article/2024/67/329/7821493

- Hutubessy R, Levin A, Wang S, et al. A case study using the United Republic of Tanzania: Costing nationwide HPV vaccine delivery using the WHO Cervical Cancer Prevention and Control Costing Tool. BMC Medicine. 2012. https://bmcmedicine.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/1741-7015-10-136#Tab4

- Slavkovsky R, Mvundura M, Debellut F, et al. Evaluating potential program cost savings with a single-dose HPV vaccination schedule: A modeling study. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr. 2024;2024(67):371-378. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC11555269/#tblfn2

- Burger EA, Campos NG, Sy S, et al. Health and economic benefits of single-dose HPV vaccination in a Gavi-eligible country. Vaccine. 2018;36(32Part A):4823-4829. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC6066173/